When Closer was released on July 18, 1980, two months after Ian Curtis’s death, it was the end of Joy Division, and the beginning of their mythos. A desolate masterpiece that practically invented the vocabulary of emotional collapse in music, Closer is considered one of the greatest post-punk records ever made. But beyond the stark tombstone of its sound lies a collection of untold stories and fascinating footnotes. Here are five of them.

When Joy Division’s Closer landed on July 18, 1980, it became a farewell, a sonic tombstone, and the deepest echo of a voice already silenced. Released two months after Ian Curtis’s death, the album transformed grief into atmosphere, cementing its place as one of post-punk’s most chilling masterpieces. But beneath the frozen surface are stories you might not know. Here are five of them.

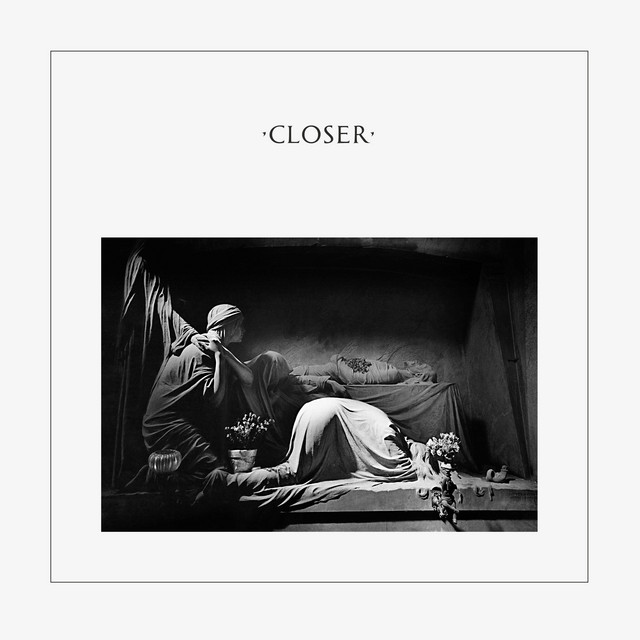

1. The Album Cover’s Tomb Was Pure Chance, Not a Plan

The marble tomb that defines Closer’s artwork came from a 1978 photo of a sculpture in an Italian cemetery. Designers Peter Saville and Martyn Atkins had picked the image long before Ian Curtis died. After his death, Saville panicked, thinking people would assume it was a tasteless marketing stunt. But Factory Records moved forward, embracing the eerie coincidence. The result is one of the most haunting album covers in music history, made even more powerful by how accidental it all was.

2. Ian Curtis Described Writing the Lyrics as a Possession

Bernard Sumner recalled Ian Curtis saying the words on Closer felt like they were writing themselves. Ian spoke of being trapped in a kind of whirlpool, dragged downward by forces he couldn’t name. This wasn’t poetic exaggeration. Songs like “The Eternal” and “Decades” carry that sensation of drowning in something far bigger than personal sadness. The lyrics came with a sense of inevitability, like Ian was merely the vessel through which they passed.

3. “Atrocity Exhibition” Was the Sound of Instrumental Role Reversal

To break creative monotony, Bernard Sumner and Peter Hook swapped instruments during the writing of “Atrocity Exhibition.” Hook played guitar, Sumner played bass, and the result was a riff that felt off-kilter and dangerous. The title came from J.G. Ballard, whose psychological collapse stories matched the tone perfectly. When Martin Hannett mixed the track while Hook was out of the studio, he drenched the guitar in effects, flattening its violence. Hook was furious, but that tension remains baked into the track.

4. “Isolation” Survived a Studio Disaster Thanks to Hannett

“Isolation” began with Stephen Morris’s electronic beat and Sumner’s high-pitched synth stabs. But disaster nearly struck when a junior engineer mishandled the master tape. Martin Hannett salvaged it through sheer sonic precision, and the end result became one of the band’s most forward-looking tracks. The crashing drums and eerie space within the mix opened a doorway to where New Order would eventually go. It’s a reminder that chaos can sometimes give birth to clarity.

5. Tony Wilson Had Poolside Dreams, Bernard Had Doubts

When Closer was finished, Factory Records founder Tony Wilson told Bernard Sumner he’d be drinking cocktails poolside in Los Angeles within a year. Sumner laughed. Joy Division didn’t operate on dreams of stardom or chart glory. They created out of necessity, out of a need to express what couldn’t be said in daylight. While Closer did chart and win Album of the Year from NME, its power came from its refusal to conform. It was bleak, unflinching, and utterly committed to its vision.

Closer is a message in a bottle sent from the darkest corners of the human psyche. These lesser-known stories remind us that great records are shaped by accidents, panic, misunderstandings, and ghostly whispers. Step inside — just like Ian said.