By Darryl Sterdan of Tinnitist

MUSCLE SHOALS, ALA. — Hallowed ground is in the eye — and sometimes the ear — of the beholder.

Your idea of a holy place might be a church, a shrine or some other place of worship — somewhere that sacred songs are sung and heaven feels a little bit closer. For others, it might be a historical site or monument — a spot where heroes and icons made history or changed the world as we know it. But when I think of hallowed ground, I naturally think of the musical landmarks where all of the above occurred — world-famous recording studios.

Thanks to my job, I’ve had the pleasure and privilege of visiting more than a few of these magical sites. I have stood in the cathedral-like magnificence of Capitol Studio A in Hollywood while Phil Everly told me about touring with Buddy Holly. I’ve lounged in the womb-like confines of Jimi Hendrix’s Electric Lady Studios in Greenwich Village, listening to rare Pink Floyd recordings. I’ve toured Sun Studio in Memphis and stood where Elvis did. I’ve seen inside Nashville’s historic RCA Studio B, where countless country hits were tracked. I’ve walked the zebra crossing in front of London’s Abbey Road. I’ve perused the gear inside Third Man Records’ mastering stuite in Nashville. And each time, I’ve felt the aura of the place, the electrical charge that still hangs in the air from everything that’s happened there.

Recently, I got to cross more names off my studio bucket list when I was offered a trip to Muscle Shoals, Alabama, the home of two of the south’s most famous and influential recording facilities — FAME Studios and Muscle Shoals Sound Studio — along with a preview tour of Muscle Shoals: Low River Rising, a new exhibit at the Country Music Hall Of Fame And Museum about two hours up the road in Nashville. Obviously, I knew a fair amount going in — along with all the music, I’ve seen the 2013 documentary Muscle Shoals: The River That Sings more than once. And I have read plenty of books on the artists who recorded there and the musical history of the region (including Peter Guralnick’s 1986 offering Sweet Soul Music, the definitive tome on the tale — at least, until fellow Canadian Rob Bowman’s new book Land Of 1,000 Sessions arrives next year). But obviously, the best way to learn about a place is to go there, see it for yourself and talk to people who know the inside story. So that’s what I did. And here are 20 things I learned on my pilgrimage:

1 | Neither studio is actually located in the city it’s named for.

Rick Hall’s FAME Studios (it stands for Florence Alabama Music Enterprises) is really situated in the neighbouring city of Muscle Shoals, while Muscle Shoals Sound Studio can be found in nearby Sheffield. Confused? Don’t be; FAME took its name from its first home, while MSSS was named for the members of the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section (later The Swampers), who opened their own studio after leaving FAME over a contract dispute. And just for the record, Florence, Sheffield and Muscle Shoals are part of a quad-city community commonly known as The Shoals. The fourth city? Tuscumbia. But ‘The Tuscumbia Sound’ doesn’t really have a ring to it, does it?

2 | FAME was originally located in a cotton field.

Nowadays, it’s surrounded by far more modern businesses — including a Pizza Hut right next door, a CVS in the rear, and both an AutoZone and a Walgreens across the street. To be honest, that seems weird — like seeing a McDonald’s on top of Mount Rushmore. (In fact, the McDonald’s is around the corner and three blocks up, past the Dunkin’.) Muscle Shoals Sound, meanwhile, is in a quieter area, with a church just down the block and a cemetery across the road. So at least you know they aren’t bothering the neighbours.

3 | Everyone who’s anyone has recorded at FAME and Muscle Shoals Sound.

You probably already know about Aretha Franklin and Wilson Pickett and The Rolling Stones and Paul Simon and The Staple Singers. But the list of artists who cut tracks here is an almost endless who’s who of music: Bob Dylan, Rod Stewart, Eric Clapton, Glenn Frey, Carlos Santana, Julian Lennon, Boz Scaggs, Bob Seger, Willie Nelson, Lynyrd Skynyrd, Gregg Allman, Duane Allman, Dire Straits, James Brown, George Michael, Jimmy Buffett, Joan Baez, Linda Ronstadt, Cat Stevens, Traffic, Joe Cocker, Lulu, John Hammond, Leon Russell, Laura Nyro, JJ Cale, Bobby Womack, Tony Joe White, Mac Davis, Canned Heat, Johnny Rivers, Paul Anka, Jose Feliciano, Lloyd Price, Kim Carnes, Dr. Hook, Delbert McClinton, Phoebe Snow, Levon Helm, Eddie Rabbit, Southside Johnny & The Asbury Jukes, John Prine, Helen Reddy, Roger McGuinn and Chris Hillman, Jerry Jeff Walker, The Oak Ridge Boys, the Amazing Rhythm Aces, The Osmond Brothers, Steve Cropper, Bobby Blue Bland, Alabama, Mink DeVille, Clutch, Sawyer Brown, Duane Eddy, John Hiatt, Widespread Panic, Melissa Etheridge, Chris Stapleton, Lana Del Rey, The Black Keys, Jason Isbell, Drive-By Truckers, The Raconteurs and even Jimmy Cliff — to name just a few.

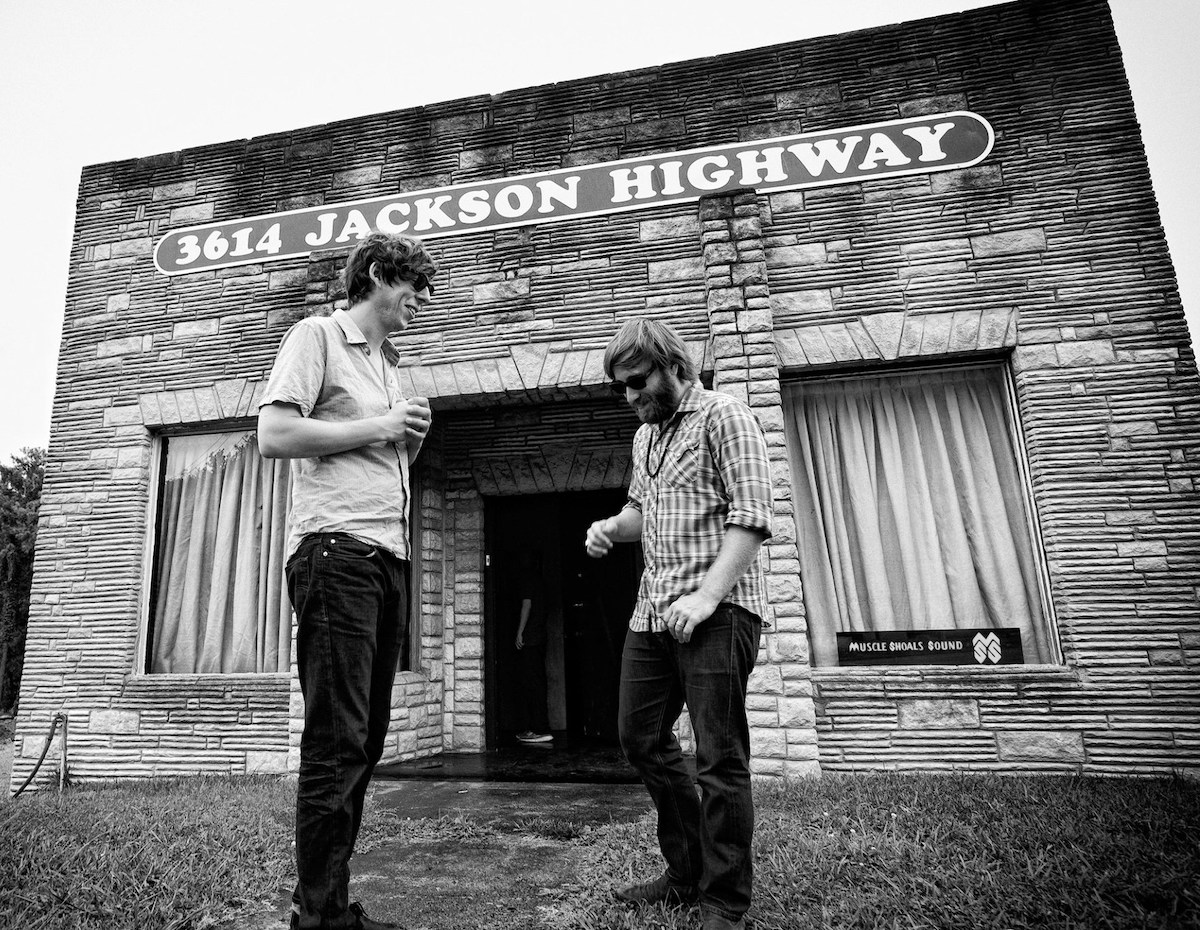

4 | The album cover for Cher’s 3614 Jackson Highway album inspired the iconic Muscle Shoals Sound Studio sign.

The album art for the singer’s sixth studio album — the first full-length LP recorded at studio in 1969 — is a black-and-white photo with her front and center, backed by The Swampers (guitarist Jimmy Johnson, bassist David Hood, drummer Roger Hawkins and keyboardist Barry Beckett), producer Tom Dowd and backup singers (including Donna Jean Thatcher, who went on to sing for The Grateful Dead under her married name Godchaux). Above them is the album title (and the studio’s actual address) encased in a blue-ish cigar-shaped sign. In reality, the building had no sign. The graphic was created by an artist. (You can see the actual street number in the left-hand window.) Being no fools, The Swampers soon ordered a sign to match the album art.

5 | The Rolling Stones paid a grand total of $1,009.75 to record Wild Horses at Muscle Shoals Sound on Dec. 4, 1969.

They paid $877.50 for 13.5 hours of studio time at $65 per hour (with Swampers guitarist Johnson behind the board); $40 for three 1″ reels of multi-track recording tape; $10 for a reel of 1/4” tape (for the mixed-down recordings); and $2.25 for three empty 5” tape reels (presumably to hold copies of the finished songs from the 1/4” tape). A facsimile of the invoice — made out to their then-manager Allen Klein’s ABKCO Industries — is prominently displayed in the studio. If they paid about the same for the other two songs they cut during their three-day visit — Brown Sugar and You Gotta Move — MSS made about $3,000. You can watch them recording in the studio in the 1970 documentary Gimme Shelter.

6 | FAME has been operating at the same location since 1961. Muscle Shoals Sound? Not so much.

The original Jackson Highway facility closed in 1979 and the owners relocated to a newer and larger facility nearby, which they sold in 1985. Even though the original building was no longer a working studio, acts like Band Of Horses and The Black Keys rented it to record there for a time. Eventually, the building housed an electronics retailer, then a used-appliance store. By 2013, it had apparently been empty for some time and was in danger of being demolished.

7 | The 2013 documentary Muscle Shoals: The River That Sings changed everything.

Directed by Greg Calamier, the film offered a reverent, revealing and somewhat romanticized version of the Muscle Shoals story. It rightly focused on OG / GOAT Hall, but also featured interviews with most of The Swampers (some in front of their abandoned building) and many artists who recorded there. When it was released, tourists began to flock to the studios. Hall, who had refused to allow tours to keep the facility from turning into a museum, relented when he saw how much money could be made. “After the documentary, they just started lining up,” says FAME’s current president and co-owner Rodney Hall, Rick’s son. Meanwhile, Muscle Shoals Sound Studio was rescued from wrecker. The Muscle Shoals Music Foundation, chaired by the younger Hall, bought the building and eventually restored it to its former glory, recreating it as it was during The Swampers’ heyday while also embracing the tourists. “We restored it do its original state, right down to this ugly orange carpet,” laughs Judy Hood — wife of Swampers bassist David, the last surviving member of the group — while sitting in the building’s basement lounge. “They don’t make carpet like this anymore. There’s a pretty good reason for that.”

8 | Dr. Dre helped save Muscle Shoals Sound.

Yes, that Dr. Dre — the N.W.A co-founder and producer / mentor of Snoop Dogg and Tupac. The Compton g-funk icon was moved by seeing the Muscle Shoals documentary, Judy Hood says. “Three months to the day after we signed the papers for this building, Dr. Dre saw the documentary in a small theatre in Santa Monica, California. He knew all about most of the Shoals music, but he didn’t know the back stories. And he was so captivated that he decided that night on the spot to start a philanthropic wing of Beats Electronics and to call it Sustain The Sound. And the mission to Sustain The Sound would be to take iconic facilities like this one and restore them. So by the next week he had people from his office talking to us about how we could get this deal done.” Eventually, Beats donated between $700,000 and $1 million to aid in the restoration, which was completed in 2017. More importantly than the money, “his heart was in it,” Hood says.

9 | Muscle Shoals Sound isn’t much bigger than it looks in pictures.

The building is longer than it is wide, but even so, it’s cozy, to be diplomatic. The studio occupies most of the main floor, with the control room at the back, and the tape machine out in the hallway by the back door. It’s so cramped that artists often listened to playbacks and mixes while standing outside on the rear stairwell — “the listening porch,” as it’s known. The publishing offices were located downstairs, along with a musicians’ lounge (complete with bar) found behind a secret hidden door (the studio used to be located in a dry county).

10 | Muscle Shoals Sound has a bathroom right in the middle of the recording studio.

Supposedly, Mick Jagger and/or Keith Richards locked themselves in there during their session to finish the lyrics to Wild Horses (though given their proclivities at the time, one suspects they were also up to other things behind that closed door). There’s a toilet seat mounted above the washroom door, pointing toward the floor like an upside-down horseshoe — because “the good shit flows down,” as one of The Swampers supposedly quipped.

11 | Swampers bassist David Hood’s gear is still in the studio — and still in use.

In the corner Hood used to occupy (right next to the drum booth, of course), you’ll still find his amp, tuner and some basses — right under an acoustic tile on which he wrote ‘David Hood was here from 1969-1978 playing bass. Underneath, a sign has been added: ‘And in February 2019 for Nicole Too,’ presumably referring to singer Nicole Atkins’ Italian Ice album, which was recorded there.

12 | Paul Simon thought The Swampers were black Jamaicans.

In 1973, the legendary singer-songwriter was interested in recording at Muscle Shoals Sound with The Swampers after hearing them behind The Staple Singers on I’ll Take You There. “I don’t know the exact story, but either Paul or his manager called (Stax Recods’) Al Bell… and said he wanted to record with the black Jamaican musicians who played on I’ll Take You There,” bassist Hood has said. “As I understand it, Al said, ‘I can give you their number, but they’re mighty pale.’ ” Perhaps Simon was confusing them with The Harry J. All Stars, the actual Jamaican band whose 1969 song The Liquidator has, well, let’s say something in common with the Staples’ 1972 recording. In any case, Simon cut much of his Rhymin’ Simon album there with The Swampers — including the hits Kodachrome and Loves Me Like A Rock — and also used the band on his next album Still Crazy After All These Years. Clearly, he got beyond the pale.

13 | Lynyrd Skynyrd’s Sweet Home Alabama — the song that made The Swampers famous — was not cut in Muscle Shoals.

In 1971 and ’72, Ronnie Van Zant and co. cut an album — including early versions of Free Bird, Gimme Three Steps, Simple Man and other future classics — at Muscle Shoals Sound with Swampers guitarist Johnson producing. But those recordings were shelved, and the band later recut them with producer Al Kooper in a Georgia studio for their 1973 debut (Pronounced ‘Lĕh-‘nérd ‘Skin-‘nérd). When it came time to record their sophomore album, 1974’s Second Helping, the band wanted to thank The Swampers for their early support and penned the now-familiar verse — “Now, Muscle Shoals has got the Swampers / And they’ve been known to pick a song or two (Yes, they do) / Lord, they get me off so much / They pick me up when I’m feelin’ blue / Well, now, how ’bout you?” The night they recorded it in Georgia, they phoned Muscle Shoals Sound, recalls Judy Hood. “Roger (Hawkins, The Swampers’ drummer) answered the phone, and the guys were like, ‘Hey, we just wrote a verse in this song for you.’ And Roger said, ‘Oh, that’s nice.’ Later on he laughed and said, ‘They just made my whole career, and all I could say was, ‘That’s nice.’ ” But nobody could have guessed at the time it was going to become so famous. It immortalized The Swampers. Anywhere we go in the world, everybody knows The Swampers.”

14 | Mavis Staples names Swampers bassist Hood in I’ll Take You There.

At about the 1:50 point in the song — when Hood switches from the song’s signature bassline to play a brief spotlight higher up the neck — Staples gently eggs him on: “David, little David, easy now, come on little David.” Most people think she’s saying “Baby” or “Lady” — including the folks who created the official lyric video for the song below — but if you listen closely on a good stereo or hear it with the vocals boosted and more isolated (as you do on the studio tour), you can hear it pretty clearly.

15 | George Michael first recorded Careless Whisper with The Swampers.

In 1983, the Wham! frontman arrived at Muscle Shoals Sound with Atlantic Records producer Jerry Wexler to cut his new track. It seemed logical — Michael was influenced by soul, Wexler had a relationship with the studio, and The Swampers were at the top of their game — but the results weren’t up to snuff. The Muscle Shoals Sound version of Careless Whisper sounds more like the ’70s than the ’80s. It feels slightly slower, smoother and slinkier. Michael, unsatisfied with the version, recut it a few weeks later in London. The original eventually surfaced on the B-side of a 12″ single.

16 | FAME’s Rick Hall was something of a packrat.

Along with all the musical instruments, recording gear, records and awards you’d expect to find in a recording studio, FAME is jam-packed with mementoes of Hall’s life and career covering every wall and surface: Pictures and letters, promo items and souvenirs, an antique gramophone and barber chair, liquor bottles, even a gold-plated ceremonial revolver and Hall’s old flip-phone. And as Rodney Hall pointed out, they’ve already donated most of their old paperwork — contracts, royalty statements, letters and more — to The Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame. Still, “we have so much stuff after 65 years that we don’t have room for it,” he says, admitting even he doesn’t know everything that’s in the place. “You open a drawer and something falls out. I open a filing cabinet and I’ll be in there for three or four hours.”

17 | Even in death, the notoriously difficult Rick Hall’s employees are still a little scared of him.

Among the countless items inhabiting Hall’s office is an old toolkit, sitting on the floor against the wall behind his barber chair, and under a framed picture of Hall with Capricorn Records co-founder Phil Walden and former U.S. president Jimmy Carter. The toolbox has been there for years, our guide mentioned. On a recent tour, a woman asked him what exactly was in it. He didn’t know, he replied; he’s never opened it. Why not? He pointed out the hand-written label on the box: Hands Off — Rick’s Tools. “I ain’t touching that,” he said.

18 | If you ask nicely, Rodney Hall might show you FAME’s tape vault.

I did, and he did. And while it was tinier than I expected — one small office-sized room — it was a sight to behold: Metal shelves stuffed with tape boxes containing original recordings of Wilson Pickett, Gregg Allman, Duane Allman, Jason Isbell, Steven Tyler, Waylon Jennings, Candi Staton, Clarence Carter and more. Hall let me take a couple of souvenir photos, but asked me not to print them, so I won’t.

19 | You can still record in the same room as Aretha Franklin or The Rolling Stones — using the same gear and even some of the same session players.

Based on their rich legacies, I would have assumed that both FAME and Muscle Shoals Sound would be out of reach for the average musician. But folks at both facilities told me they’re open for all kinds of business — and more affordable than comparable studios in Nashville (though prices have gone up since the Stones’ days). FAME books tours early in the morning and late in the afternoon to stay out of the way of musicians — there was a group working in the main studio during my visit — while MSSS is primarily open for tours, but books sessions in the evening, and on Sundays and Mondays.

20 | There’s plenty to do in The Shoals besides visiting studios.

I honestly didn’t know what to expect when I arrived in the area. But I know this: I didn’t expect to stay in a music-themed Renaissance resort — complete with a revolving restaurant at the top of a tall tower, one of the world’s largest collections of Rolling Stones memorabilia on site, and a TV station that broadcasts the Muscle Shoals doc 24/7. I also didn’t expect to find that the area has plenty more fantastic restaurants serving up everything from southern cuisine to sushi, along with cool bars, boutique hotels, a charming downtown and plenty of parks. Another thing I discovered: I can still put away a 14-oz New York steak. This was my first visit; it won’t be my last.