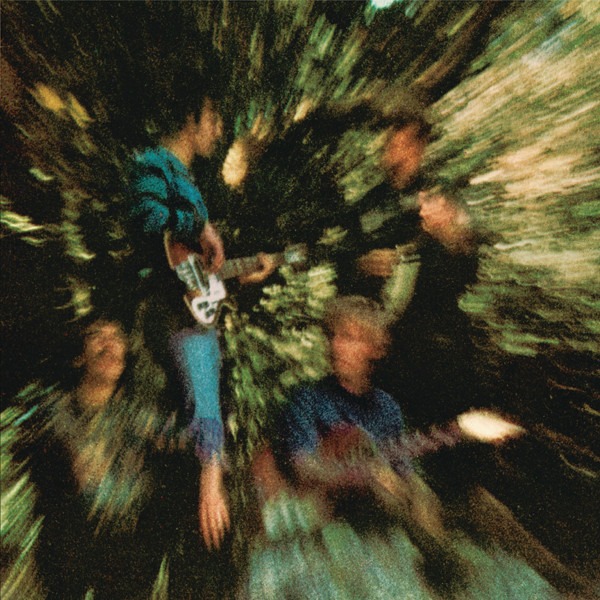

Creedence Clearwater Revival defined the sound of swamp rock with the 1969 release of their second studio album Bayou Country. Despite being California natives, the band—led by the singular vision of John Fogerty—crafted a gritty, Southern aesthetic that resonated with a factual sense of rural authenticity. The album was the first of a staggering three LPs the group released that year, peaking at number seven on the Billboard 200 and spawning the immortal hit “Proud Mary.” Recorded at RCA Studios in Hollywood, the project balanced raw club energy with meticulous studio overdubbing, all while tensions simmered over John Fogerty’s total creative control. Their transition from their struggling years as the Golliwogs to this chart-topping dominance deserves to be dug in a bit deeper.

The Beethoven Opening Influence

John Fogerty intentionally looked toward classical music for the dramatic opening of his signature hit, “Proud Mary.” He was a fan of Ludwig van Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 and wanted to open the song with a similarly powerful, descending musical gesture. This led to the creation of the famous repeated C chord to A chord progression that kicks off the track. By blending this classical inspiration with an attempt to emulate the guitar style of Steve Cropper, Fogerty created a factual bridge between orchestral weight and Southern soul.

Blank Wall Meditation

The atmospheric opener “Born on the Bayou” was composed in a very sparse, beige-walled apartment where John Fogerty would sit and stare at the blank slate for hours. Lacking the funds for paintings or distractions, he used the silence and the ringing sound of his overdriven amp to enter what he described as a meditative, other-dimensional state. This intense focus allowed him to conjure hoodoos and swampy imagery despite having never lived in the American South, proving the power of his imagination as a songwriter.

The Carwash Confrontation

Despite their newfound success with “Susie Q,” the band was on the verge of breaking up during the Bayou Country sessions. A major confrontation erupted when the other members demanded more input into the arrangements and songwriting. John Fogerty, however, was terrified of returning to his pre-fame life at the carwash and insisted on assuming total control to ensure the band’s longevity. This autocratic approach was so intense that during a dispute over the melodic quality of the backing vocals for “Proud Mary,” Fogerty recalled that the group “literally coulda broke up right there.”

A Stolen Gibson Masterpiece

For the recording of “Born on the Bayou,” John Fogerty utilized a specific Gibson ES-175 guitar with an overdriven amp and a slow tremolo setting to achieve that “greasy” swamp rock tone. Factually, this iconic instrument was stolen from Fogerty’s car shortly after the track was completed. This loss marked a poignant end to the session, as the stolen guitar had been the primary tool used to capture the soulful, rhythmic feedback that drummer Doug Clifford cited as the beginning of the song’s unique “quarter note” beat.

The Real Proud Mary Ship

While the song has biblical and epical implications for many listeners, the title refers to a real piece of American history. The Proud Mary, more formally known as the Mary Elizabeth, was an actual ship based in Memphis, Tennessee, that traveled along the Mississippi River for fifty years, from 1928 to 1978. Fogerty combined this historical reference with fragments of other songs—including one about a washerwoman named Mary—to tell the story of a working-class narrator finding salvation and rebirth on the water.