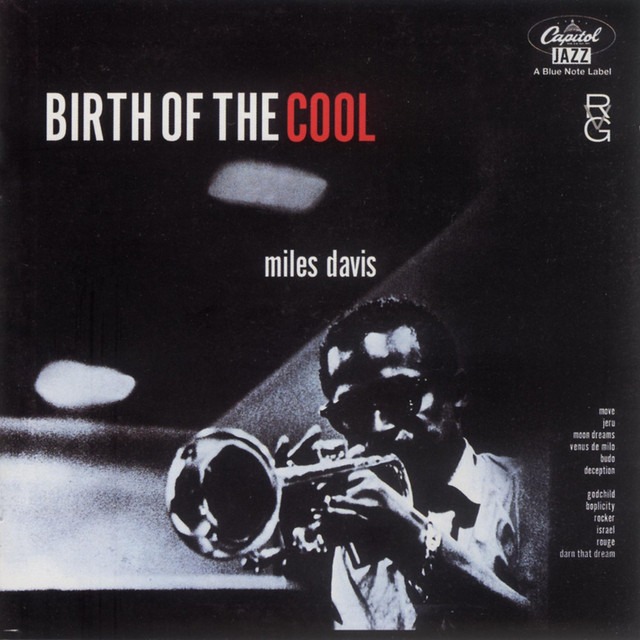

Miles Davis orchestrated a pivotal shift in the history of modern music with the recordings compiled in the 1957 masterpiece ‘Birth of the Cool’. Seeking an alternative to the high-speed intensity of bebop, Davis assembled a groundbreaking nonet to explore a more lyrical, relaxed, and “cool” sonic palette. Influenced by European classical techniques and the impressionist textures of the Claude Thornhill orchestra, the group utilized unusual instrumentation—including the tuba and French horn—to blend voices like a choir. These sessions, recorded across three dates between 1949 and 1950, effectively birthed the cool jazz movement and established a new standard for musical arrangement. Every three-minute track on this project reflects a factual commitment to innovative harmony and instrumental balance. Witnessing the transition from Davis’s early days with Charlie Parker to this sophisticated, low-vibrato sound is a definitive highlight for any student of jazz history.

The Smallest Large Orchestra

Miles Davis intentionally designed his nonet to be the smallest possible group of instruments that could still capture the rich, impressionistic harmonies of the 18-piece Claude Thornhill Orchestra. He found the larger big band format too cumbersome for his creative vision and chose to split the group in half to achieve a more intimate sound. This technical choice allowed the ensemble to use “paired instrumentation,” where trumpet and alto saxophone would sing the melody together while the tuba and baritone saxophone provided a revolutionary counterpoint.

The 55th Street Basement Brainstorm

The conceptual framework for the album was developed during late-night gatherings at arranger Gil Evans’s small basement apartment on 55th Street in Manhattan. Evans kept an “open door policy,” hosting forward-looking musicians who wanted to move away from the “thrusting and parrying” style of traditional big bands. These sessions served as a factual laboratory where the participants discussed the future of jazz, adopting tools from European impressionist composers to create a more fluid and choral-like instrumental texture.

A Piano-Less Final Session

During the third and final recording date on March 9, 1950, the nonet took the experimental step of performing without a piano for most of the session. This omission allowed the unique textures of the French horn and tuba to stand out more prominently against Davis’s midrange trumpet work. Despite a year-long gap since their previous studio date and having zero rehearsals or live performances in between, the band captured legendary tracks like “Moon Dreams” and “Deception” with a remarkable sense of cohesion.

Cleo Henry’s Secret Identity

The track “Boplicity,” widely considered one of the most significant pieces of the era, was a collaboration between Miles Davis and Gil Evans. However, the song was originally credited to the pseudonym “Cleo Henry.” This was a factual nod to Davis’s mother, as he used her name to secure the composer credits while working outside of his usual contractual obligations. The song remains a benchmark for the album’s sound, featuring the non-vibrato playing style that would become a hallmark of cool jazz.

The “Not Really Jazz” Controversy

Upon its initial release, the nonet’s sound was so revolutionary that some contemporary critics struggled to classify it. Winthrop Sargeant of The New Yorker famously compared the music to the work of Maurice Ravel and stated that it was “not really jazz” due to its fastidious tone color and aural poetry. Even the short-term public reaction was relatively quiet, but the long-term impact proved to be massive, as the album eventually earned a perfect 10/10 from Pitchfork and was credited with launching an entire subgenre.