By Gabriel Szatan

Two students of astrophysics and architecture walk into a bar on the moon. This sounds like the beginning of a joke — but in the waning light of the 20th century, it really happened, leaving a serious imprint on pop culture.

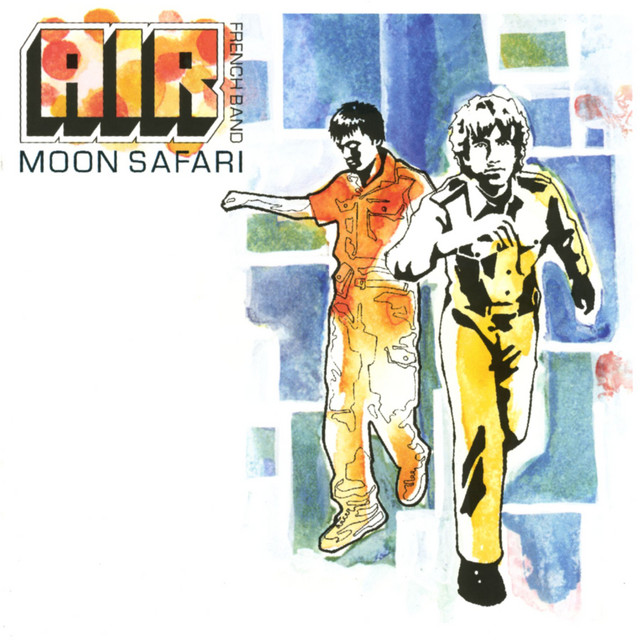

On January 16th 1998, Air released Moon Safari, an album which catapulted Nicolas Godin and Jean-Benoît Dunckel to the uppermost rung of electronic music’s ladder. Their sound — Fender Rhodes trills, loping basslines and sensual-yet-playful vocal hooks, all woven into a texture as fine and luxe as chiffon — conjured the sensation of a space-age cocktail designed to be supped at leisurely pace. It’s not challenging to see how this curious little record became a global sensation.

“The hype was a violent experience,” reflects Jean-Benoît Dunckel, 25 years later. “Air’s music is not accessible or easy to discern: The format is strange, the voices are strange, the subjects are strange. Even ‘Sexy Boy’ sounds strange. We were a duo doing some electronic thing, dreaming of selling 10,000 copies and being recognised by other musicians as cool. Then suddenly, we met the world. Personally, it took me time to see that we could be a big, important band.”

Formed in 1995 from the remnants of prior rock outfit Orange, Air’s debut album was a paradox made flesh. Here were two 20-somethings with just a single prior EP under their belts, yet they exuded on tape the confidence and pedigree of seasoned pros. The English press deemed them acutely French; meanwhile, the French press pondered if they might actually be English. Although their influences were unusual and ambitions they were avowedly anti-commercial, Godin and Dunckel were blessed with the ability to intuit pop songcraft which could, and did, captivate mass media.

In short, Moon Safari was a nest of contradictions. Today, the record’s legacy is canonical, but at the time of release, its multi-million success was far from assured.

“This kind of bedroom music was all about fantasy,” says Nicolas Godin. “In my mind, I was picturing myself at Capitol Records, surrounded by all the best musicians, feeling like Burt Bacharach. In reality, I was in the fucking 18th arrondissement of Paris, with a sampler, singing into one microphone. But when your fantasy is so strong, I think it goes in the wires and through the speakers. The power of Moon Safari was to make people believe in what we believed in.”

During Moon Safari’s gestation in 1996-97, a “new wind of freedom and creativity was carrying through the same creative part of Paris,” recalls Dunckel. “And it was not only in music — graphic design, cinema and fashion were alive.” This spark of youthfulness and sense of renewed pride in French creation encouraged Air to push beyond the proggy Moog-fixation exhibited by stars of the previous generation, such as Jean-Michel Jarre and Magma, while also simultaneously avoiding the aromanticism of cheap, raved-up synthesiser zaps.

Instead, according to Godin, Air’s own mirepoix boiled down to a few core ingredients. Ravel and Debussy informed the “dreaminess, floating chords and heritage of pre-rock music” you might be able to detect. That sense of silver-screen flair came from the grooves of John Barry and Ennio Morricone. As for the tempo? Portishead.

“Suddenly, all the things I liked and was good at — slow, downtempo soundtrack music — could bring success. We were not formulating success itself. But until 1994, I was listening to the radio and thinking, ‘There’s no way I will make it; whatever this sound of today is, it is not me.’ But then, I heard Portishead’s Dummy on the radio — and thought to myself: ‘…I can make that.’”

Though far from club hounds, Godin and Dunckel were still attuned to the sensation of riding out a night’s highs into the vaporous sprawl of mid-morning. Moon Safari found as much purchase as the comedown record du jour as it did for any other function. In no time at all, Air’s downtempo influence was easy to detect all around.

From the mellowed-out sketches of late-period Stereolab and departure- lounge exotica of The Avalanches to — at the other end of the valorous scale — ten-a-penny chillout compilations, the relative peace which marked the late 1990s and early 2000s offered a moment to slow down and reflect; to lean into a sonic mode which Dunckel now summarises as “a deep, universal spell, full of love and mystery.”

While Air’s precise alchemy and absence of geographical anchoring placed Moon Safari outside the grip of temporality or trend, the album happened to be an orbiting satellite which intersected with the world below’s revolutions at precisely the right moment.

Through Moon Safari, Air transfixed some of the great visionaries of the late 20th century — David Bowie, Madonna, Beck — as well as influencing preeminent aesthetes of the incoming age — including Charlotte Gainsbourg, Kevin Parker and Sofia Coppola, whose creative relationship with Air became as synergetic as that of Angelo Badalamenti and David Lynch (another fan, while we’re here.)

Air helped fan the flames of a rare Francophilia which surging through the typically nativist British charts in 1998. Moon Safari birthed three hit singles in “Kelly Watch The Stars,” “All I Need” and “Sexy Boy,” shifted over half a million copies in the UK, and pushed Air into headline contention at banner festivals such as Glastonbury. This in turn brought American, European and even hesitant French audiences and critics in line, a ripple effect which continued into the mid-2000s, with a string of successive top 10 albums for Air, at home and abroad.

It also bundled Air into a promotional game they were, by their own accounts, rather unequipped for. Enlisting a young Phoenix to thrash around as their backing band for TV appearances was, with the benefit of a quarter-century’s wisdom, perhaps an unwise decision. This moment of vibe vandalism, Thomas Mars has since said with impish delight,“kind of ruined Air…we destroyed their sound.” (Smiles on both Dunckel and Godin’s faces confirm there are no hard feelings.)

25 years on, it’s not hard to alight upon why Moon Safari has stood the test of time. Air’s unique grasp of pace and mood, surety of direction, and earworm hooks compelled the world toward it, and in turn propelled Air on toward posterity.

The duo’s early surprise that their outerzonal fantasies might capture international hearts and minds has since melted into a sense of deep gratification. Unbeknownst to them, millions stood by their televisions, radios and record players, waiting to receive this particular longwave transmission from somewhere in the cosmos.

But moreover, the satisfaction arises from executing such a precise studio vision with zero concessions. On an artistic level, Air achieved exactly what they set out to do; their mission was a resoundingly successful one.

“To me,” Godin concludes, “Moon Safari is perfect.”