In everything he did, John Lennon spoke his truth and questioned the truth. An incomparable and uncompromising artist who strove for honesty and directness in his music, he laid bare his heart, mind and soul in his songs, seeing them as snapshots of his current emotions, thoughts and world view. Believing the one quality demanded of himself as an artist was to be completely honest, he did not disguise what he had to say or conform his messages to be more in line with what he felt others thought they should be. Love, heartbreak, peace, politics, truth, lies, the media, racism, feminism, religion, mental well-being, marriage, fatherhood – he sang about it all, and one just needs to listen to the songs of John Lennon to know how he felt, what he cherished, what he believed in, and what he stood for.

On October 9th, 2020, Lennon’s 80th birthday, in celebration of his remarkable life, a collection of some of the most vital and best loved songs from his solo career will be released as a suite of beautifully presented collections, titled GIMME SOME TRUTH. THE ULTIMATE MIXES.

Executive Produced by Yoko Ono Lennon and Produced by Sean Ono Lennon, these thirty-six songs, handpicked by Yoko and Sean, have all been completely remixed from scratch, radically upgrading their sonic quality and presenting them as a never-before-heard Ultimate Listening Experience.

Mixed and engineered by multi GRAMMY Award-winning engineer Paul Hicks, who also helmed the mixes for 2018’s universally acclaimed Imagine – The Ultimate Collection series, with assistance by engineer Sam Gannon who also worked on that release, the songs were completely remixed from scratch, using brand new transfers of the original multi-tracks, cleaned up to the highest possible sonic quality. After weeks of painstaking preparation, the final mixes and effects were completed using only vintage analog equipment and effects at Henson Recording Studios in Los Angeles, and then mastered in analog at Abbey Road Studios by Alex Wharton in order to ensure the most beautiful and authentic sound quality possible.

GIMME SOME TRUTH. – named for Lennon’s 1971 excoriating rebuke of deceptive politicians, hypocrisy and war, a sentiment as relevant as ever in our post-truth era of fake news, will be available in a variety of formats including as a Deluxe Edition Box Set that offers several different ways to listen to this engrossing 36-track collection with stunning new mixes across two CDs alongside a Blu-ray audio disc containing the Ultimate Mixes in Studio Quality 24 bit/96 kHz HD Stereo, immersive 5.1 Surround Sound and Dolby Atmos.

“John was a brilliant man with a great sense of humour and understanding,” writes Yoko Ono Lennon in the preface of the book included in the Deluxe Edition. “He believed in being truthful and that the power of the people will change the world. And it will. All of us have the responsibility to visualize a better world for ourselves and our children. The truth is what we create. It’s in our hands.”

The 124-page book included in the Deluxe Edition has been designed and edited by Simon Hilton, the Compilation Producer and Production Manager of the Ultimate Collection series. The book tells the story of all thirty-six songs in John & Yoko’s words and the words of those who worked alongside them, through archival and brand-new interviews, accompanied by hundreds of previously unseen photographs, Polaroids, movie still frames, letters, lyric sheets, tape boxes, artworks and memorabilia from the Lennon-Ono archives.

GIMME SOME TRUTH. will also be released as a 19-track CD or 2LP, a 36-track 2CD or 4 LP, and several digital versions for download and streaming including in 24 bit/96 kHz audio and hi-res Dolby Atmos. The vinyl was cut by mastering engineer Alex Wharton at Abbey Road Studios. The Deluxe Edition and 4LP formats will include a GIMME SOME TRUTH. bumper sticker, a two-sided poster of Lennon printed in black and white with silver and gold metallics, and two postcards, one of which is a replica of Lennon’s letter to the Queen of England in 1969 when he returned his MBE in “protest against Britain’s involvement in the Nigerian-Biafra thing, against our support of America in Vietnam and Cold Turkey slipping down the charts.” The 2LP and 2CD will also include the poster and all versions will come with a booklet filled with photos and the MBE letter.

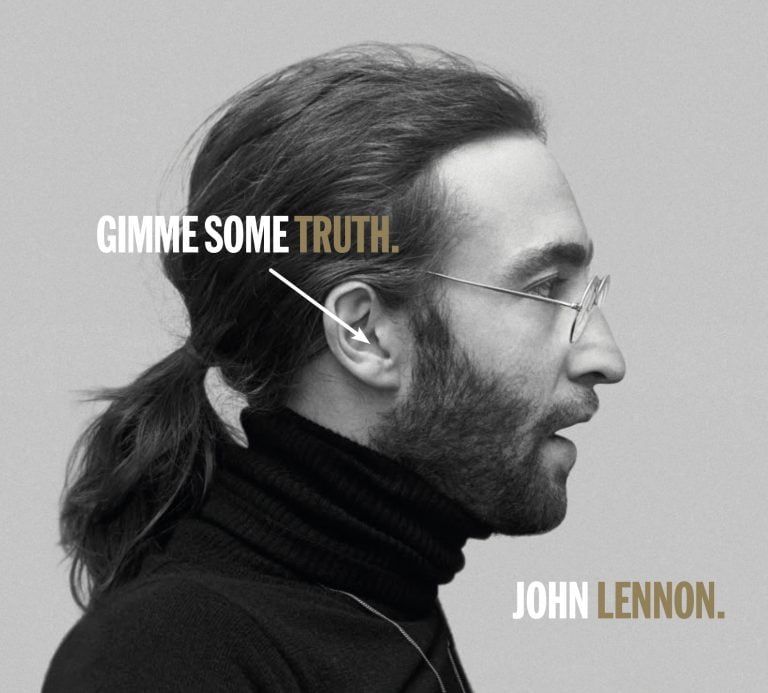

The album cover features a rarely seen striking black and white profile portrait of John Lennon, taken on the day John returned his MBE. The album cover, CD and LP booklets and typographic artworks were designed by Jonathan Barnbrook who created the covers for David Bowie’s albums Heathen, Reality and The Next Day and won a GRAMMY® Award for the packaging of Bowie’s Black Star album.

GIMME SOME TRUTH. traces the arc of Lennon’s post-Beatles life and career, bringing together songs from all of his revered solo albums including John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band (1970), Imagine (1971), Some Time In New York City (1972), Mind Games (1973), Walls and Bridges (1974), Rock ‘n’ Roll (1975), Double Fantasy (1980) and 1984’s posthumous Milk and Honey. The collection is bookended with his early non-album singles, kicking off with the one-two punch of “Instant Karma! (We All Shine On),” Lennon’s exuberant exhortation about the karmic forces of action/reaction and equality (“we all shine on like the moon and the stars and the sun”), and the electrifying addiction-themed “Cold Turkey,” and culminating with the holiday classic “Happy Xmas (War Is Over)” and the anti-war protest anthem “Give Peace A Chance,” with its ubiquitous, titular call to action: “All we are saying is Give Peace A Chance.”

Sequenced in chronological order by album they were released on, songs on the 36-track version include all of Lennon’s biggest hits and showcase his thoughts, beliefs and convictions about everything from peace (“Imagine,” “Give Peace A Chance,” “Happy Xmas (War Is Over)”), religion (“God”), politics (“Power To The People,” “Working Class Hero”), lying politicians (“Gimme Some Truth”), racism (“Angela”), equality (“Woman”), love and marriage (“Love,” “Oh Yoko!,” “Dear Yoko,” “Mind Games,” “Out The Blue,” “Every Man Has A Woman Who Loves Him,” “Grow Old With Me”), fatherhood (“Beautiful Boy (Darling Boy)”), loneliness (“Isolation”) and much more. Some of the many other highlights include the sonically sumptuous “Jealous Guy” and “#9 Dream,” the acerbic “How Do You Sleep?,” the breezy, carefree “Watching The Wheels,” a rollicking live recording of “Come Together” that he had originally recorded with The Beatles, the rapturous Elton John collaboration “Whatever Gets You Thru The Night,” and the jubilant, bittersweet “I’m Stepping Out.”

Like all Lennon projects, intense thought and care went into the making of GIMME SOME TRUTH. and the remixing of these treasured songs. As Paul Hicks details in the Deluxe Edition book: “Yoko is very keen that in making The Ultimate Mixes series we achieve three things: remain faithful and respectful to the originals, ensure that the sound is generally sonically clearer overall, and increase the clarity of John’s vocals. ‘It’s about John,’ she says. And she is right. His voice brings the biggest emotional impact to the songs.” Hicks continues, “The combination of remixing from all the original first-generation multitrack sources and finishing in analogue has brought a whole new level of magic, warmth and clarity to the sound, along with a more detailed dynamic range and sound stage, and we really hope you enjoy the results.”

The results speak for themselves and allow Lennon’s voice and words to shine on, clearer and brighter, at a time when they are needed now, more than ever. When listened to in sequence, GIMME SOME TRUTH. THE ULTIMATE MIXES. plays both like one of the greatest-ever live Lennon concerts and an emotional telling of his life story, from just after the breakup of The Beatles, to falling in love and marrying Yoko, his peace activism, personal soul-searching, inspiration, celebration, confusion, reunion, fatherhood, his five-year break from music while raising Sean, and his triumphant return into the ‘80s with two new albums.

Throughout these incredible, timeless songs we experience the many facets of John Lennon: the songwriter, the revolutionary, the musician, the husband, the truth-teller, the dad, the provocateur, the peace activist, the artist, the icon.

JOHN LENNON. GIMME SOME TRUTH. THE ULTIMATE MIXES.

2 CD + 1 Blu-ray audio disc (24 bit/96 kHz Stereo, 5.1 Surround Sound, Dolby Atmos) and 124-page book

CD1

1. Instant Karma! (We All Shine On)

2. Cold Turkey

3. Working Class Hero

4. Isolation

5. Love

6. God

7. Power To The People

8. Imagine

9. Jealous Guy

10. Gimme Some Truth

11. Oh My Love

12. How Do You Sleep?

13. Oh Yoko!

14. Angela

15. Come Together (live)

16. Mind Games

17. Out The Blue

18. I Know (I Know)

CD2

1. Whatever Gets You Thru The Night

2. Bless You

3. #9 Dream

4. Steel and Glass

5. Stand By Me

6. Angel Baby

7. (Just Like) Starting Over

8. I’m Losing You

9. Beautiful Boy (Darling Boy)

10. Watching The Wheels

11. Woman

12. Dear Yoko

13. Every Man Has A Woman Who Loves Him

14. Nobody Told Me

15. I’m Stepping Out

16. Grow Old With Me

17. Happy Xmas (War Is Over)

18. Give Peace A Chance

BLU-RAY AUDIO DISC

All of the above thirty-six tracks, available in High Definition audio as:

1. HD Stereo Audio Mixes (24 bit/96 kHz)

2. HD 5.1 Surround Sound Mixes (24 bit/96 kHz)

3. HD Dolby Atmos Mixes

4 LP

LP 1 SIDE A

1. Instant Karma! (We All Shine On)

2. Cold Turkey

3. Working Class Hero

4. Isolation

5. Love

LP 1 SIDE B

6. God

7. Power To The People

8. Imagine

9. Jealous Guy

LP 2 SIDE A

10. Gimme Some Truth

11. Oh My Love

12. How Do You Sleep?

13. Oh Yoko!

14. Angela

LP 2 SIDE B

15. Come Together (live)

16. Mind Games

17. Out The Blue

18. I Know (I Know)

LP 3 SIDE A

19. Whatever Gets You Thru The Night

20. Bless You

21. #9 Dream

22. Steel And Glass

23. Stand By Me

LP 3 SIDE B

24. Angel Baby

25. (Just Like) Starting Over

26. I’m Losing You

27. Beautiful Boy (Darling Boy)

28. Watching the Wheels

LP 4 SIDE A

29. Woman

30. Dear Yoko

31. Every Man Has A Woman Who Loves Him

32. Nobody Told Me

LP 4 SIDE B

33. I’m Stepping Out

34. Grow Old with Me

35. Give Peace a Chance

36. Happy Xmas (War Is Over)

2CD / DIGITAL (DOWNLOAD & STREAMING)

CD1

1. Instant Karma! (We All Shine On)

2. Cold Turkey

3. Working Class Hero

4. Isolation

5. Love

6. God

7. Power To The People

8. Imagine

9. Jealous Guy

10. Gimme Some Truth

11. Oh My Love

12. How Do You Sleep?

13. Oh Yoko!

14. Angela

15. Come Together (live)

16. Mind Games

17. Out The Blue

18. I Know (I Know)

CD2

1. Whatever Gets You Thru The Night

2. Bless You

3. #9 Dream

4. Steel And Glass

5. Stand By Me

6. Angel Baby

7. (Just Like) Starting Over

8. I’m Losing You

9. Beautiful Boy (Darling Boy)

10. Watching the Wheels

11. Woman

12. Dear Yoko

13. Every Man Has A Woman Who Loves Him

14. Nobody Told Me

15. I’m Stepping Out

16. Grow Old with Me

17. Give Peace a Chance

18. Happy Xmas (War Is Over)

2 LP

LP 1 SIDE A

1. Instant Karma! (We All Shine On)

2. Cold Turkey

3. Isolation

4. Power To The People

LP 1 SIDE B

5. Imagine

6. Jealous Guy

7. Gimme Some Truth

8. Come Together (live)

9. #9 Dream

LP 2 SIDE A

10. Mind Games

11. Whatever Gets You Thru The Night

12. Stand By Me

13. (Just Like) Starting Over

14. Beautiful Boy (Darling Boy)

LP 2 SIDE B

15. Watching The Wheels

16. Woman

17. Grow Old With Me

18. Happy Xmas (War Is Over)

19. Give Peace A Chance

1CD / DIGITAL (DOWNLOAD ONLY)

- Instant Karma! (We All Shine On)

- Cold Turkey

- Isolation

- Power To The People

- Imagine

- Jealous Guy

- Gimme Some Truth

- Come Together (live)

- #9 Dream

- Mind Games

- Whatever Gets You Thru The Night

- Stand By Me

- (Just Like) Starting Over

- Beautiful Boy (Darling Boy)

- Watching the Wheels

- Woman

- Grow Old with Me

- Happy Xmas (War Is Over)

- Give Peace a Chance